This post has already been read 6465 times!

I’ve spoken a lot about the benefits of disruption recently, but what of the companies and people in the wake of disruption, the ones who bear the brunt of the changes and see their industry or livelihoods evaporate?

Disruption and Dissent

This is nothing new. Ever since the industrial revolution, and probably earlier, as technology has shifted, so people have been displaced. It can be painful, frustrating… even violent.

“There were many sources of disharmony… Some employers used false weights in giving out yarn and nails… Textile workers mixed butter and grease with the fabric to increase the weight.”

– The Industrial Revolution, T.S. Ashton, 1948

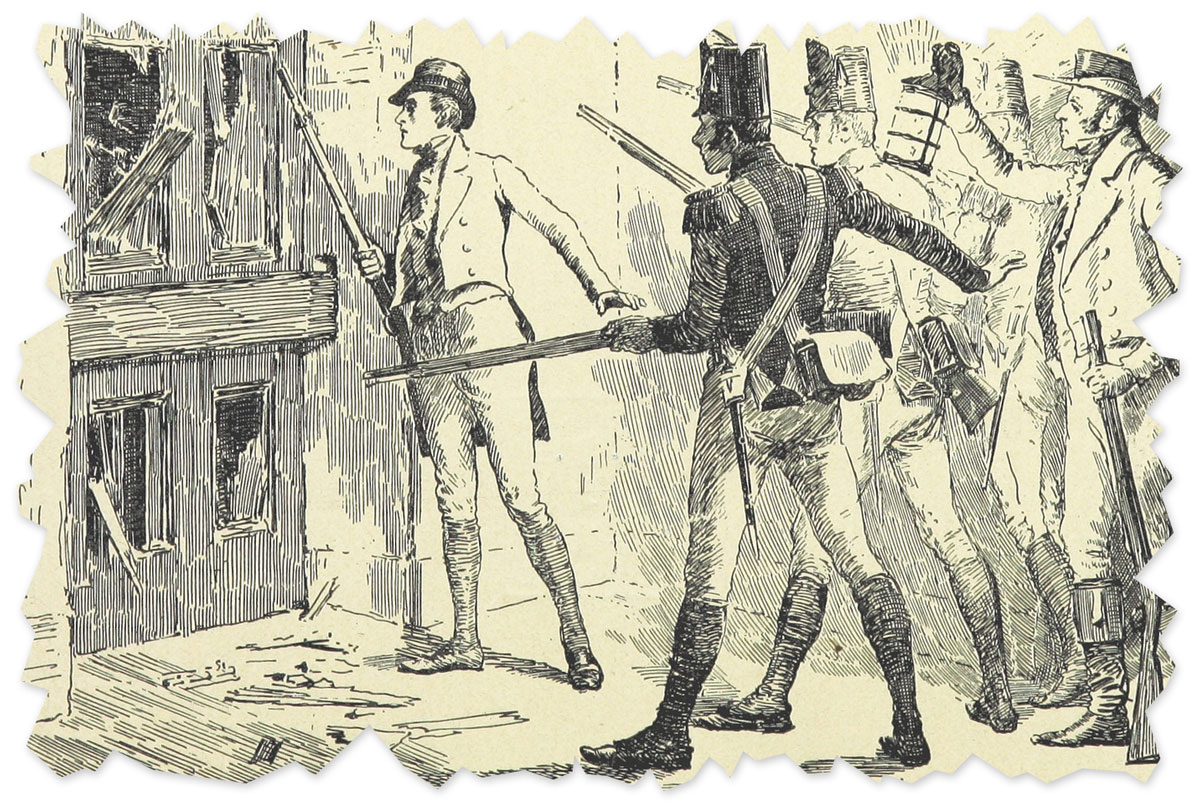

When the first rattles of mechanization began to replace weavers in the late 18th century England, discontent simmered. In 1779 Ned Ludd snapped. In a fit of rage he allegedly took a hammer to a stocking frame, and sparked the “Luddite” movement dedicated to destroying machines.

The Luddites were most active around 1811-16, when they actively planned attacks and practiced drills. They not only destroyed machines, they burned down entire mills, and on at least one occasion, assassinated a mill owner. It was so bad that industrialists had secret rooms built in to their factories so they could hide in the event of an attack. (Source: Wikipedia: Luddites)

The British Army eventually suppressed the Luddite uprising, and Parliament enacted harsh penalties which ultimately ended the Luddite movement. Yet the Luddites have been around in some form ever since.

When the automobile came along, no doubt there were cries of “But what will become of the buggy makers?” Such pleas are heard every time innovation disrupts an industry, even today, when we should know better.

Ned’s hammer has been replaced with legalities. The neo-Luddites are lobbyists, taxis drivers versus Uber, auto dealers versus Tesla, hotels versus AirbnB, retailers versus Amazon.

Displacement is Temporary

The truth is, people who are displaced will do something else, many will move on to better things. They will no longer work inefficiently, building obsolete products and delivering expensive services that no one wants. Instead they’ll do more meaningful and valued work, perhaps learn new skills and master new technology.

Often, the very industry that displaced them will be the source of many new jobs and opportunities. As the economist Henry Hazlitt noted:

“Before the end of the nineteenth century the stocking industry was employing at least a hundred men for every man it employed at the beginning of the century.”

(Economics in One Lesson, Henry Hazlitt, p50, Arlington House, 1979)

The market is dynamic in that respect, labor and capital flow to where it is most productive, fueling new growth and new opportunities in new industries.

Rebirth of the Rust Belt

Such a change is happening in the Rust Belt. Laura Putre has an interesting article in IndustryWeek detailing this transformation, where old manufacturing cities such as Akron, Albany and Pittsburgh, are remaking themselves as modern manufacturing and technology centers. Take Akron, Ohio:

Sixty years ago, Akron, Ohio’s rubber industry employed more than 50,000 people. But in the 1980s, as three of the four major tire companies left the city, most of those jobs disappeared. Times were dire for years, but gradually the region began to capitalize on its existing strengths—the material science expertise of its research universities, its workforce of engineers, scientists and tradespeople—and reinvent itself as the center of the polymer industry. According to statistics from the city’s website, upwards of 35,000 people in the Akron area are now employed in approximately 400 polymer-related companies.

(Source: From Rust Belt to Brain Belt)

This story of transformation and rebirth is repeated in cities such as Albany NY and Pittsburgh. Some European cities are undergoing a similar process.

What’s Driving this Rebirth?

Putre refers to an interesting new book, “The Smartest Places on Earth: Why Rust Belts are the Emerging Hotspots of Global Innovation,” which provides some answers:

“…Brain Belts’ have what emerging markets don’t: a skilled manufacturing workforce, a well-developed system of research universities and a culture of innovation.”

All three are important, but that last, “a culture of innovation,” is key and was certainly something the Luddites lacked.

So while disruption benefits everyone, it inevitably brings a certain amount of (temporary) turmoil in its wake. That “churning” can be a valuable source of new innovation and new opportunities. That is, provided we are willing to learn, work and embrace change and innovation.

For more more details on how and why the rebirth is happening, read IndustryWeek’s From Rust Belt to Brain Belt.

References

- The Industrial Revolution, T.S. Ashton, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Luddites, Wikipedia

- Economics in One Lesson, Henry Hazlitt, Arlington House Publishers, New York, 1979

- From Rust Belt to Brain Belt, Industry Week

- How to Avoid a Technology Horror Story - October 31, 2024

- How Chain of Custody Strengthens the Supply Chain - October 11, 2022

- Inside Next Generation Supply Chains - November 8, 2021